Where we’re at in the race for a COVID-19 vaccine

There are almost a dozen coronavirus vaccines in final-stage testing, with Moderna and Pfizer showing promising preliminary results. Scientists welcome the crowded field because different types of vaccines will be needed to meet global demand. (Nov. 17)

AP

Although the COVID-19 outbreak is looking worse than ever, news from vaccine makers is fueling optimism – maybe even jubilation – among experts in the field.

Normally restrained and cautious, a panel of experts convened by USA TODAY could barely contain its enthusiasm over the latest effectiveness figures from both Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech, whose vaccine candidates have been shown to be about 95% effective, while not raising any serious safety concerns.

“It’s the best news so far this year,” said Florian Krammer, a virologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

The proof of effectiveness and safety also marks a shift from the development to distribution phase of the vaccine process.

While both companies and others making vaccines depended on tens of thousands of Americans to volunteer for clinical trials, beginning as soon as next month, millions of Americans will get to choose whether to get vaccinated.

That will require sophisticated logistics: to get the vaccines delivered, get them in people's arms, remind people to come back weeks later for a second shot and record any problems.

It also will require scientists and others to convince hundreds of millions of Americans – starting with frontline health care workers – that the vaccine is a crucial tool in the fight against COVID-19.

"Having a vaccine that no one uses would be a disaster," said Peter Pitts, president and co-founder of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest, a New York-based nonpartisan think tank.

Pitts and Krammer are members of the expert panel USA TODAY has relied on for six months to gauge the monthly progress of COVID-19 vaccine development.

This month their estimate took its largest leap yet.

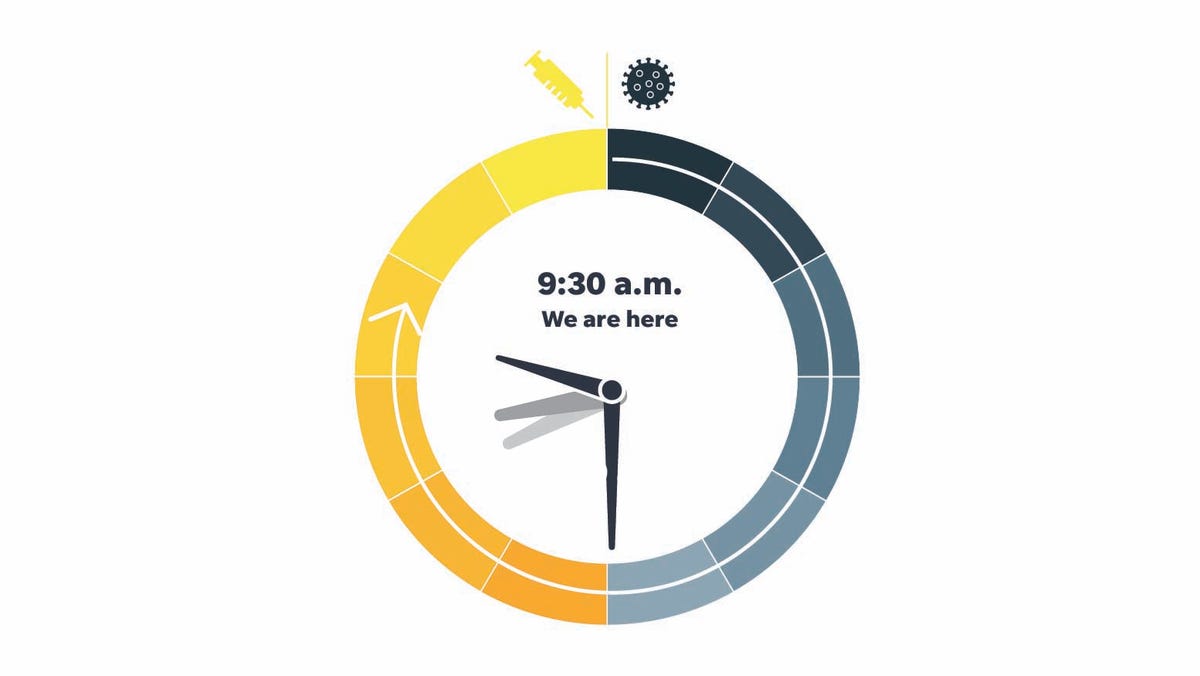

The members judge the time on a clock that began at midnight with the discovery of the dangerous new virus in early 2020, and ends at noon, when a vaccine is freely available across the U.S.

In June, the panel's first median time was 4 a.m. By last month, the sun had risen and it was 8 a.m. For November, the time shot ahead to 9:30 a.m. — the biggest forward tick so far.

The candidate vaccines have been advancing at a breathtaking pace, said Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center and an attending physician in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

If anyone had asked scientists in January, when the genome of the virus was first published, whether 11 months later two huge clinical trials showing such effectiveness and safety would have been completed, “no one would have said that was possible,” Offit said.

The irony is that developing the vaccines — with an estimated $11 billion government price tag — was considered to be most difficult. Instead, the cheapest way to stem the tide of infections, wearing masks, socially distancing and avoiding crowds, turned out to be the real challenge.

“Vaccines were the hard part. Hygienic measures, which are arguably equally, if not more powerful – that we couldn't do,” Offit said.

Coming soonish to an arm near you

A first wave of frontline medical workers could start getting vaccinated against COVID-19 this holiday season but getting a vaccine into the arms of most Americans is still a long way off, the panel said.

Authorization of one and possibly two COVID-19 vaccines is anticipated within weeks.

“That means we can begin inoculating health care and other essential workers even before we’re done with the Thanksgiving leftovers,” said Pitts, who oversaw the Food and Drug Administration's public outreach programs during the George W. Bush administration.

On Wednesday, U.S. Health and Human Services Sec. Alex Azar said[1] there will be 40 million doses of vaccine available by the end of December, enough to vaccinate about 20 million people. Frontline health care workers are expected to be at the first in line.

With two vaccines so far along, the focus is shifting from whether a vaccine is possible to how it will get out into the world, said Dr. Kelly Moore, associate director of immunization education at the Immunization Action Coalition.

“At that point, the gears driving our clock toward noon transition from vaccine research and testing to vaccine supply, vaccination program capacity, and demand,” she said.

New administration, same logistical challenges

At this point, the election of Joe Biden to the presidency won’t have much effect on vaccine development and authorization, panelists said. That speedy pace was set months ago by President Donald Trump.

“You really need to give the administration credit for doing this,” said Offit.

The change in administrations could affect America’s collective understanding of the pandemic and vaccines and their willingness to get immunized.

The first job for Biden will be convincing the 40% or so Americans hesitant about the vaccine that it’s their patriotic duty to line up for a jab, said Pitts.

“The President-Elect and Vice President-Elect should roll up their sleeves and insist on being the first two persons in line,” as soon as a vaccine is authorized, he said.

Panelists also expect a Biden administration to provide clearer and more consistent messaging about the science and safety of the vaccines — and the need to wear masks and stay physically distanced to keep infection levels down even as the vaccine is rolled out.

“We are likely to see greater focus on masks and other ‘low tech’ mechanisms for mitigating transmission,” said Duke University Law School professor and health law expert Arti Rai.

Biden has made clear he will trust science advisors and federal medical officials. That will help, said Pamela Bjorkman, a structural biologist at the California Institute of Technology.

“I think we can now look forward to the message that all decisions will be based on the science,” she Bjorkman.

Regular administration briefings on COVID-19 haven’t taken place in months. That will change under Biden, expects Moore, who is also a former member of the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

“By late January, I hope to see Dr. (Anthony) Fauci and the CDC’s top experts at the podium regularly, sharing the latest news and guidance with all of us,” she said.

It really, really works

The apparent effectiveness of both vaccines is a game-changer, said Prakash Nagarkatti, an immunologist and vice president for research at the University of South Carolina.

Nagarkatti was especially happy to see data from the Moderna clinical trials that seemed to indicate its vaccine was effective in the elderly and minorities. Because these groups have been among the hardest hit by the pandemic, a strong effective vaccine is “very encouraging,” he said.

It’s difficult to remember that only nine short months ago one big unanswered question was whether the spike protein — now so well known it shows up in cartoons and as a Halloween costume — was indeed the place to focus efforts.

“These early results suggest that they picked a great target,” said Moore, chair of the World Health Organization Immunization Practices Advisory Committee. It also means the other vaccines targeting the spike protein may be similarly successful.

To have this all happen in the space of 11 months is amazing, said Dr. Michelle McMurry-Heath, president and CEO of Biotechnology Innovation Organization, an industry group.

“The data on the effectiveness of Pfizer and BioNTech’s vaccine are extremely encouraging. The speed at which they and many other biopharma companies have mobilized to develop a vaccine is both remarkable and unprecedented,” she said.

The new vaccines may produce more antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, than recovering from a case of COVID-19 does.

“These mRNA vaccines are very unique in the history of vaccines and may lead to a more robust immune response if the body’s own machinery is being harnessed to produce a protein (S or spike protein),” said Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease expert at the University of California-San Francisco.

Their very newness also raises potential concerns, said Rai.

“Pfizer’s and now Moderna’s convincing results are a tremendous step forward. However, because a product using an mRNA platform has never been approved before, we do have uncertainty about large-scale manufacturing and distribution,” she said.

Many questions still remain as early results made public via press releases over the last two weeks were based on short follow-up times after vaccination.

“Will the vaccine only keep you from getting sick or will it also block asymptomatic infection and transmission? What will its longer-term safety record look like? Will the vaccine’s protection decline over time, and how long will it last? Despite the uncertainty, these strong early results give us confidence moving forward,” said Moore.

A long slog ahead

Even with a vaccine that works, hurdles remain. The most obvious is both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines require two shots, three or four weeks apart.

“These vaccines are also known to cause some side effects such as fever, sore arms, and muscle ache and because this is a two-dose vaccine, people may hesitate to come back if they suffer from severe side effects from the first dose,” said Dr. Gregory Poland, who directs the Mayo Clinic's Vaccine Research Group and is editor-in-chief of the journal Vaccine.

Getting all Americans full access to vaccine will take many months, in part because it’s not all yet made, in part because vaccinations take time to work, and in no small part because the logistics are daunting.

“I expect vaccines to be widely available to general public in the middle of next year, due to limited production capacities and tremendous challenges in distributing vaccines,” said Soo-Haeng Cho, a professor of operations management and strategy at the Tepper School of Business at Carnegie Mellon University.

Getting the right number of doses to hospitals and doctors’ offices all across the nation isn’t as simple as loading up planes and trucks, said Prashant Yadav, a senior fellow and medical supply chain expert at the Center for Global Development in Washington D.C.

The relationship between states and the federal government is likely to improve under the new administration, Yadav said.

“There’s a trust deficit between the states and the federal agencies running COVID-19 pandemic planning,” he said. “If that gets resolved, which it is quite likely to, it will mean more seamless planning which will make the supply chain work better when we have a vaccine.”

While it will still take time to get a vaccine to every American who wants one, the likelihood of getting there during 2021 is much greater than before,” Moore said.

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Director Dr. Anthony Fauci told the USA TODAY Editorial Board Wednesday, the general U.S. population could expect to have access to vaccine as early as April and continuing through the summer.

That hopeful outlook was echoed by Poland.

“My guess is general availability by the second or third quarter of 2021,” he said.

How we did it

USA TODAY received responses from 14 scientists and researchers, asking how far they think the vaccine development effort has progressed since Jan. 1, when the virus was first internationally recognized. Those responses were aggregated, and we calculated the median, the midway point among them.

This month's panelists

- Pamela Bjorkman, structural biologist at the California Institute of Technology

- Soo-Haeng Cho, professor of operations management and strategy, Tepper School of Business, Carnegie Mellon University

- Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease expert at the University of California-San Francisco

- Sam Halabi, professor of law, University of Missouri; scholar at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University

- Florian Krammer, virologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City

- Dr. Michelle McMurry-Heath, president and CEO of Biotechnology Innovation Organization

- Dr. Kelly Moore, associate director of immunization education, Immunization Action Coalition; former member of the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; chair, World Health Organization Immunization Practices Advisory Committee

- Prakash Nagarkatti, immunologist and vice president for research, University of South Carolina

- Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center and an attending physician in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, and a professor of Vaccinology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

- Peter Pitts, president and co-founder of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest, and a former FDA Associate Commissioner for External Relations.

- Dr. Gregory Poland, director, Mayo Clinic's Vaccine Research Group, editor-in-chief, Vaccine

- Arti Rai, law professor and health law expert at Duke University Law School

- Erica Ollmann Saphire, structural biologist and professor at La Jolla Institute for Immunology

- Prashant Yadav, senior fellow, Center for Global Development, medical supply chain expert

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

References

from GANNETT Syndication Service https://ift.tt/3pETEam

Post a Comment

Post a Comment