CINCINNATI – From the moment she saw it on TV, Paula Pierce[1] followed the story of the young woman in Utah because she saw herself. Watching the video of the woman talking with police, Pierce sensed she was making excuses for her boyfriend, as she once did.

"For 16 years, I said the good outweighed the bad, and I kept enabling him," Pierce said. "She was blaming it all on herself."

She saw fear in the woman’s eyes, fear she felt, too, fear she wished could have been eased right at the moment the woman needed help the most. Pierce understood the value of someone saying, “I understand.”

Pierce, 62, credits her life now to a groundbreaking partnership between Cincinnati Police and local nonprofit Women Helping Women, which advocates for survivors. The program, called Dvert, combats the longstanding policing problem of domestic violence – a crime that comes with shame and the worry that no one will listen, a crime that doesn’t always stop when the police take the perpetrator away in handcuffs[2].

Dvert program combats domestic violence

Dvert puts domestic violence advocates right beside police officers when someone calls for help. When someone called police on Gabby Petito and her fiancé in Utah, only law enforcement responded. In Cincinnati, the call would also have summoned someone with a social services background.

Since 2018, police can call in a Dvert advocate through county dispatch to a domestic violence situation. On a police-issued radio, the advocate lets everyone know help is on the way. Advocates bring resources to survivors, including assistance with finding childcare or a safe place to stay and even groceries. They can help survivors apply for protection orders.

In 2020, Dvert advocates made nearly 1,000 runs, and program leaders expect even more this year. Women Helping Women raises money through grants and other means to pay for the expansion and train advocates.

Beyond the Bruises: How domestic violence can have an intergenerational legacy[3]

One afternoon in February, when Pierce’s boyfriend was arrested for threatening her with a metal pipe, a Dvert advocate arrived at her Cincinnati house within minutes of police. At that moment, Pierce recalled, “I just thought, ‘I think I'm going to be OK. I think I can get through this.’ ”

An expertise police don't have

A public hungry for police reform can consider co-response programs such as Dvert. Police remain the first resort for social problems from homelessness to mental health episodes, while activists argue police are not the right tool for those problems – and many officers agree. Co-response programs can get the right resources to the right people.

Since a flurry of civil unrest in Cincinnati in 2001, police have been under scrutiny to change and adopt best practices. This brought about a longstanding partnership with UC Health that dispatches mental health professionals to scenes when needed.

"We need social services out there because they provide that level of expertise that is missing with the police," said Lt. Col. Mike John, who leads the patrol bureau of Cincinnati police.

John came across a co-response program for domestic violence in Arizona in 2016. He reached out to Women Helping Women, which for years had partnered with the department and collected domestic violence incident reports to reach out to survivors. But information was getting lost, and help came too slowly. In the first 24 hours after an incident, John said, relatives can pressure a survivor to avoid court or downplay the violence.

Kristen Shrimplin, president and CEO of Women Helping Women in Cincinnati, said her organization long saw the gaps.

"Law enforcement had shown up multiple times, but (the victims) have never had a safety plan. They've never been connected, if they wanted to, with the courts for a protection order. They've never gotten case management. They've never just even been on a hotline call to get that support."

After more than a year of preparation and a $100,000 grant from the Ohio attorney general, Dvert launched in 2018. "In 2017, I believe there were 12 domestic violence murders in the county, nine of those in the city," Shrimplin said. "It was such a pain point that when we came together we said, 'OK, what more can be done?' That's when there was that real willingness to try something new."

Domestic violence homicides up 62% in Ohio

Shrimplin and others say the need for such help has only grown with the pandemic. Domestic violence homicides are up 62% in Ohio. Experts believe stay-at-home orders, changing childcare and school needs and additional economic stress have contributed.

Dvert’s primary goal is saving lives by stepping between abuser and survivor. But Shrimplin and law enforcement say there are other positive effects. Since advocates can provide services to survivors and their children in an effort to break the intergenerational legacy. Cincinnati police Sgt. Hollis Hudepohl has seen this happen firsthand while working with Dvert on the street.

“I think violence in general is increasing in our society. There was the old slogan in the domestic violence movement, it's ‘Peace on Earth begins at home,’ ” Hudepohl said. “A lot of people are being raised with violence and they're not getting help. So it is becoming more prevalent.”

The legacy of domestic violence

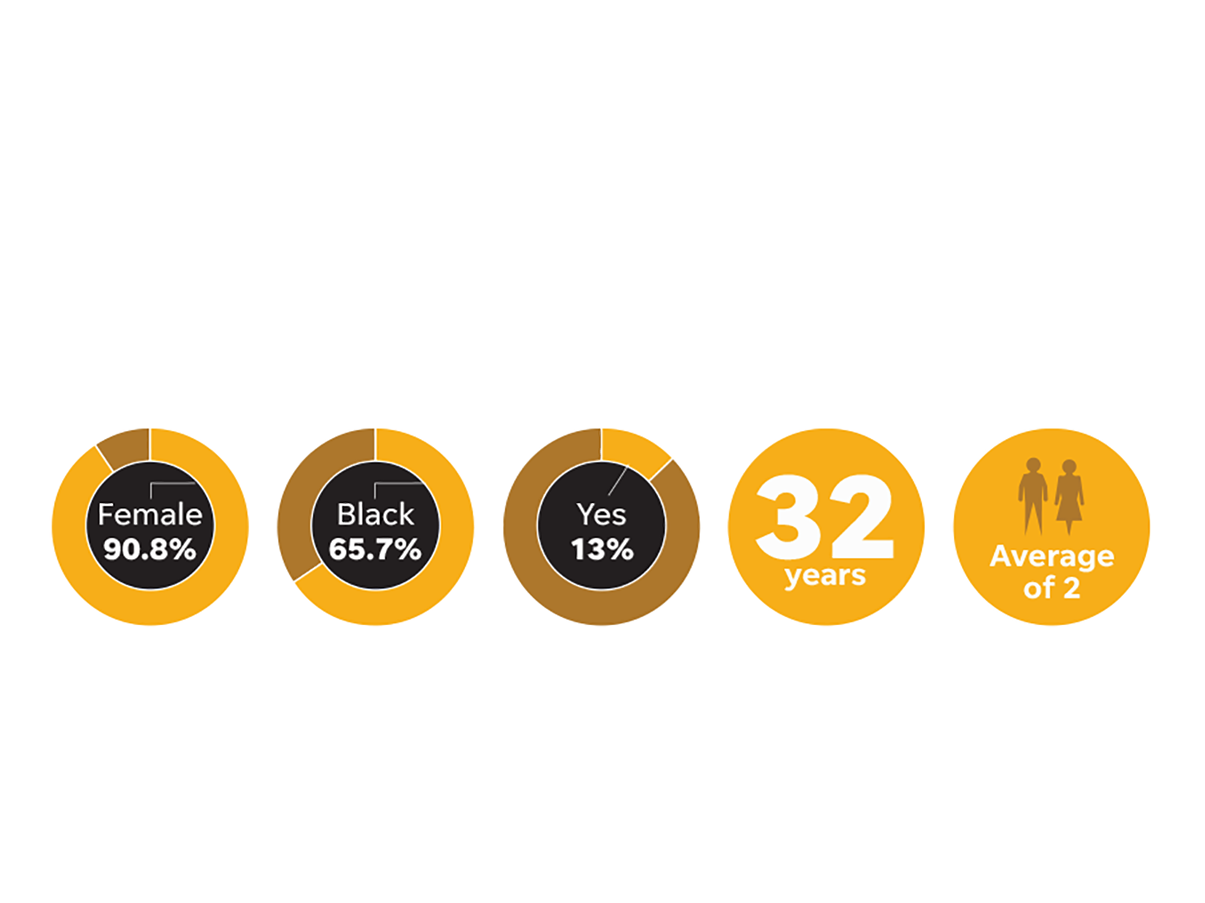

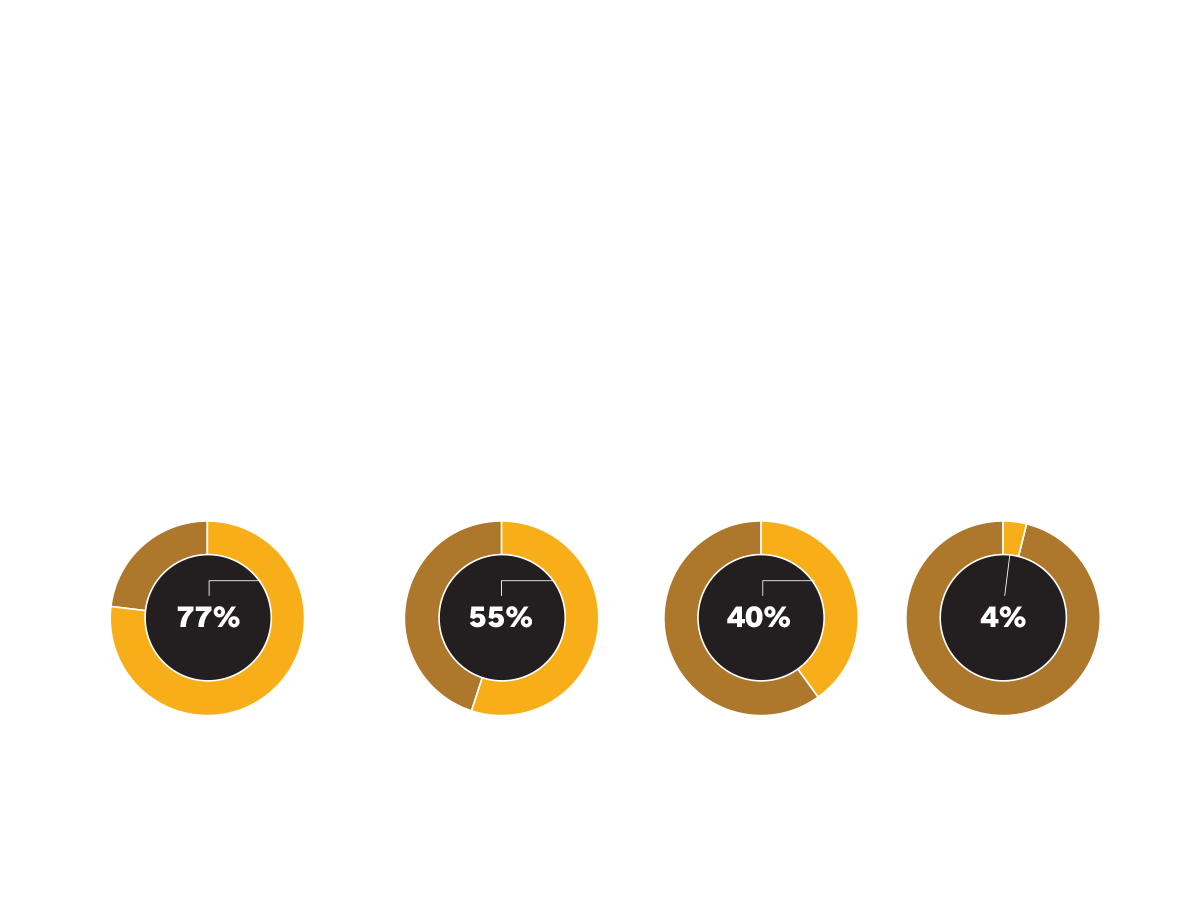

In April 2020, six women were murdered in Cincinnati, more than in all of 2019, an analysis of domestic violence offenses showed.[4]

The analysis by the Cincinnati Enquirer, part of the USA TODAY Network, found a quarter of perpetrators and survivors in those cases had in childhood or adolescence known a close relative, often a parent, who had been arrested for domestic violence.

Pierce’s struggles have carried through the generations of her family. She was estranged from her father and forced to flee her husband. In 2003, she met Shane Fulmer while working a clerical job at a Cincinnati homeless shelter. Fulmer was a client. When they met, Pierce recalled, Fulmer just looked so sad.

They were together for 16 years. "He would do everything around the house,” she said. “I couldn't even wash a dish, I couldn't do anything. I thought he was taking care of me for all these years."

But Fulmer would disappear for days on drug binges, Pierce said, and he slowly pulled her away from her family. Though rarely physically abusive, he spoke cruelly. "He got drunk one time and told me that if I died, he wouldn't even shed a tear."

Pierce struggled with her health, and she believed Fulmer was caring for her. Early this year, she caught COVID-19. While she lay bedridden for weeks, she said, Fulmer told her friends and family she might die. She said she later learned he was selling her belongings. She now believes he was over- and under-dosing her with her medications.

When Pierce recovered, two friends took her out for lunch and bought her groceries. When they came back to her home, she said, Fulmer was waiting with a metal pipe in his hand. She said he lost his temper, threw the groceries across the apartment, dumped her medication, threw her cat and threatened Pierce and her friends.

Cincinnati's kids: Childhood trauma can lead to violence, and many of Cincinnati's kids are traumatized[5]

"He just had me beside myself," Pierce said. "I was just following him around and crying." As she called 911, she said, Fulmer leaned in and said, "If I go to jail, when I get out, I'll kill you."

"Did I just hear that?" she recalled the dispatcher saying.

Within the hour, police had taken Fulmer away, and a Dvert advocate arrived. Pierce doesn't remember much of what she said, but she remembers how nice she was. The advocate gave her two $25 gift cards to replace the groceries.

That night, Fulmer tried to call her from jail, but Pierce found the courage to turn him out of her life. "I'll tell you what, when I hit block all calls, it was like this giant weight lifted off my shoulders, you know, like I didn't have to hear him talk and pretend like he was sorry anymore."

An advocate went to court with Pierce for every hearing. Another walked her through the application for a protection order. The advocates were always available to talk, Pierce said.

Fulmer was convicted of aggravated menacing and spent 30 days in jail. He violated the protection order by repeatedly trying to contact her.

Alone in her apartment, Pierce worried that Fulmer would show up, or worse, that she might relent and take him back. But she knows the advocates are a phone call away, and, "They actually have empathy. They actually care. They actually have advice and they have resources.

“If that lady hadn't have come that day, I believe he'd be right here."

After Pierce first spoke to the Cincinnati Enquirer, Fulmer was found dead on the streets of Cincinnati on Oct. 21. His cause of death is pending.

Pierce said the police contacted her because he had a note in his pocket with her contact information on it. She said her first instinct was to blame herself, but she immediately reached out to those people who supported her through this entire ordeal.

When Fulmer was still out there, she kept her apartment dark and shades drawn. The day after he died, she drew back the curtains.

"I want to get some light in this dark room," she said.

Getting police officers on board

Dvert had some growing pains, John said. It took time for officers to get in the habit of calling for the advocate, but eventually, officers saw victims were getting help, and trust was built. John said the services Dvert advocates provide are "absolutely critical."

The challenges facing domestic violence survivors are formidable, said Hudepohl, who spent years as a social worker before joining the police force.

"Some women are working, they have no family. The abuser is helping them watch the kids, or maybe they're going to their abuser's mother's house," Hudepohl said. "You can just see that weigh on their mind, ‘If I go through with this, I'm not going to have a babysitter. I'm not going to have help.' "

Police officers have embraced Dvert, Hudepohl said, because it works. She said officers get disheartened to go to the same homes and break up the same fights over and over. Officers feel helpless arresting the same violent person multiple times only to have charges dropped because the victim doesn’t appear in court.

Hudepohl said Dvert gets more women to show up by standing beside them every step of the way. While police can react to crime, they don't have resources to help survivors safely remove themselves from a relationship, which, Hudepohl said, is “the worst time in a relationship. That's when you can be killed.

"Dvert is there to say, 'You know, courts are great, but let's come up with a plan.’ “

Shrimplin says it’s too early to know Dvert’s impact on policing domestic violence and court management of cases. But other successes are apparent: Around 70% of Dvert-assisted survivors had no previous connection with any social service agency.

Pandemic side effect: Domestic violence spikes, grows more deadly[6]

"It already transformed from a pilot study," Shrimplin said. "Now (Dvert) is being described as evidence-based (and) should be replicated nationally because it works in the measurements that we're looking at."

Shrimplin said Dvert is expanding as quickly as it can. Money is the limiting factor, and changes to the national Victims of Crime Act have caused belt-tightening across the country for non-profits that work with domestic abuse survivors. Women Helping Women depends heavily on grants to make Dvert happen.

Answering the next survivor's call

Wayne Williams’ phone rang at almost anytime, but most often at night. He answered, then flipped on the police radio and jumped in his car. A survivor needed him.

Williams has worked in nonprofits for nine years, with the incarcerated, those suffering from substance abuse and mental health problems. Then he landed at Women Helping Women and was among the first Dvert advocates. Later he became the program’s director.

Williams said he prepares for the worst when he responds, and he tells the paid, trained advocate force to do the same.

"What I do and what I suggest my staff to do is put on music while you drive into the scene just to relax you a bit because you don't know what you're walking into," he said. "I probably put on my favorite R&B song."

On the scene, Williams gets background from the responding officer, so the survivor doesn’t have to repeat the story. When he meets the survivor, he introduces himself and adds, “No need to rush, I have nothing but time."

Then he listens and tries to figure out how to help. He also keeps an eye out for children and usually has a teddy bear or a toy for them.

Williams said much of Dvert’s success is apparent in chatter on police radios. Officers across the county can hear calls for Dvert advocates, they hear advocates check-in and give their reports. Because of this police in other jurisdictions have radioed for Dvert even when their department doesn't have a partnership with Women Helping Women, which can lead to some slightly awkward conversations.

Williams said this shows that the little snippets of the conversations officers hear over the radio are enough to convince cops that Dvert helps.

From his own life, Williams said he knows how important a survivor advocate can be in a crisis.

"I was once that child who grew up in a domestic violence household where there wasn't anyone there but the officer and my mother,” he said. For Dvert “to actually be on scene and provide comfort to children as well as a survivor, that's one of the reasons why I do this work. We're showing up in real time."

References

- ^ Paula Pierce (bit.ly)

- ^ doesn’t always stop when the police take the perpetrator away in handcuffs (bit.ly)

- ^ How domestic violence can have an intergenerational legacy (www.usatoday.com)

- ^ an analysis of domestic violence offenses showed. (www.usatoday.com)

- ^ Childhood trauma can lead to violence, and many of Cincinnati's kids are traumatized (www.cincinnati.com)

- ^ Domestic violence spikes, grows more deadly (www.cincinnati.com)

- ^ 10 umbrella events (www.cdc.gov)

from GANNETT Syndication Service https://ift.tt/3Cg5pKp

Post a Comment

Post a Comment