Sometimes the boy[1] needed to get away, from family and the bustle of a busy house. And so he’d set out, into the sugar maples and birches and American beeches that give New York's Catskill Mountains their spring and summer green and their autumn fire.

He'd head north, in the High Woods section of Saugerties, New York. In no time, the trees would clear.

Then he’d see the man in the quarry.

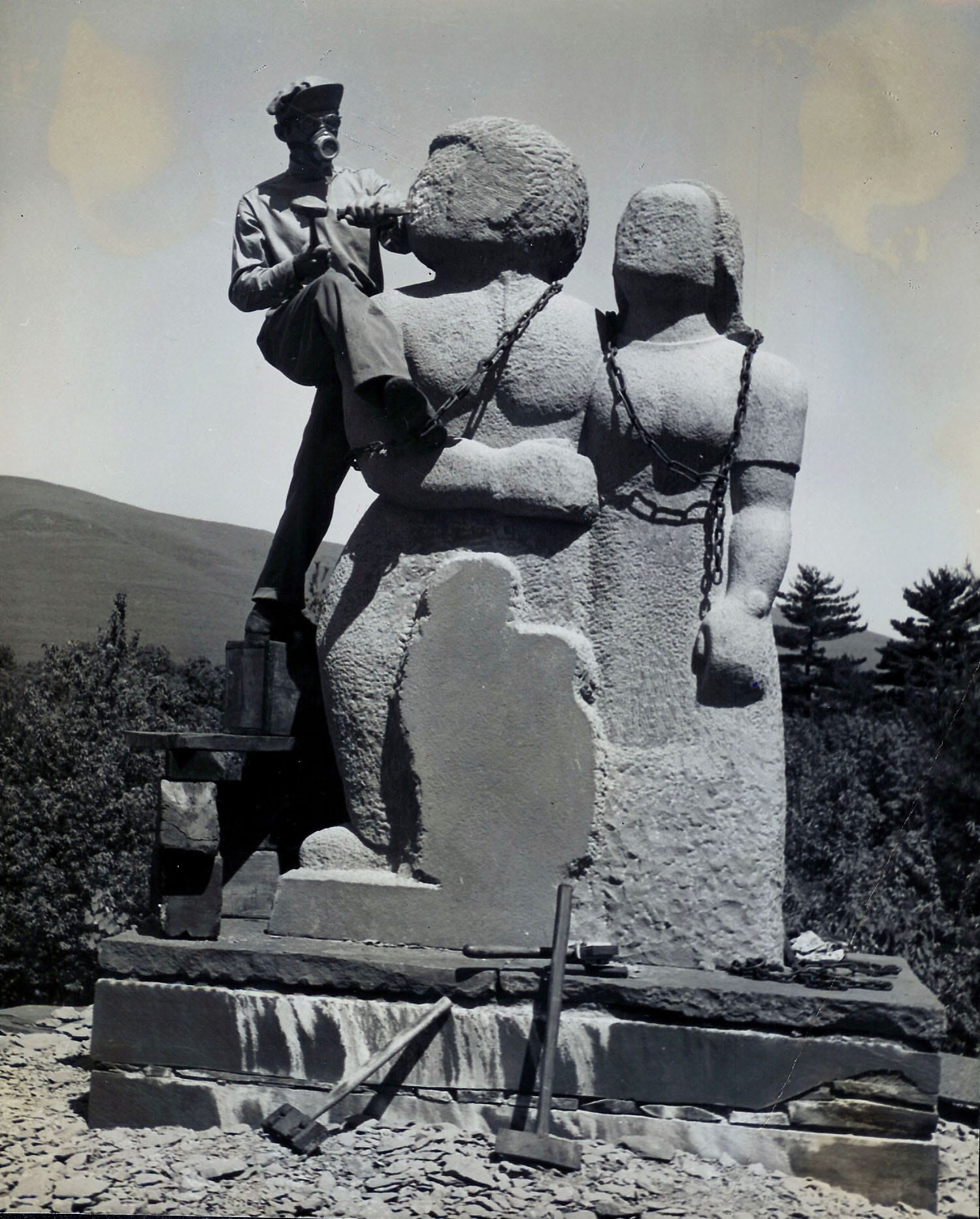

The man was nearly always shirtless, in shorts and boots, the summer sun leathering his skin. He labored alone, singularly focused, stacking flat rocks into a maze of platforms and paths, ramps, walls and terraces around the sleeping quarry.

Sometimes the boy would see him lasso a huge slab of stone with a rope and use a wooden derrick to hoist and swing it into place.

The man was assembling a three-dimensional puzzle for which there was no photo for reference, no blueprint, no plan, and no mortar to hold his monumental sculpture garden together.

The boy had a front-row seat every summer for the last decade or so of the garden's construction. He watched the man work in solitude, endure rock slides, tear down some sections and rebuild them as he got better at his labor.

The man, Harvey Fite, began with one idea: to singlehandedly make a sprawling 6½-acre canvas on which to display the sculptures he created. But he came to understand that his true art was the pedestal itself.

Some have called what he created "America's Stonehenge." He called it Opus 40, because he figured it would take him 40 years to finish. He made it to 37½. Using chisel, sledgehammer and, as he liked to say, no technology more advanced than a carpenter's level, he toiled away in pursuit of his singular obsession.

Today, thousands of visitors a year stand spellbound, mouths agape, at what he created, the scale of it all.

One man made this.

As he worked, his dark hair swept by the wind, the muscles in Fite’s powerful legs, back and arms hardened until his body resembled the chiseled angles and strong lines of the rock with which he worked. In winter, he would sculpt indoors, perhaps in wood.

But every summer, for the better part of 40 summers, Harvey Fite turned to stone.

The man chip-chip-chipped away with the rock hammer and chisel, locking a flat stone into the stones around it, something he’d learned at Copán, the Mayan restoration in Honduras, the year he’d bought the quarry.

Twelve acres for $250 in 1938; $25 down, the rest to come.

The Mayans mastered dry-key construction as far back as 400 A.D., stacking stone on stone, held together by gravity alone, with large stones adding stability.

Harvey Fite worked without talking. There would be time to talk when the workday was done, when he’d relax with his wife, the daughter of a famous muralist, and she'd read aloud to her dyslexic husband in the home he built on the edge of his creation.

Sometimes, while working, he would look up and see the boy watching him; he'd wave, then return to his task, placing stones.

One day, the boy asked if he, too, could place a stone.

“Well, no, John,” Fite told the 9-year-old. “This is one man's piece of art."

Then he added: "But if you want to grab a rake and clear out some leaves ...”

The boy leaped to it, honored. Later, he got to thinking, “I could sneak in there at night and place a stone, and who's to know?”

But there was something about the man — beyond the fact that he and his wife were his parents’ friends and neighbors — that made that sort of trickery unthinkable to the boy. He later confessed his thought to the man, who smiled.

“John, honor is a man's gift to himself,” Fite said, quoting Rob Roy, the Scottish folk hero. Then he tousled the boy’s hair and went back to work.

Harvey Fite died 45 years ago, ultimately doomed by the same gravity that holds his garden together. But that long-ago boy — John Cederquist, who is now 63 — has carried that lesson with him: Honor is a man’s gift to himself.

Cederquist has become a Fite acolyte, serves on the site's nonprofit board, leads tours of Opus 40, deepening visitors' understanding of what they are seeing, what it took to create, and the puzzle pieces that made up the man who dreamed and stacked and willed it into being.

When he talks about Fite's method of working, he calls it "Harvey's way."

No one who knew Harvey Fite when he was young would have predicted he'd do anything for 37½ years straight.

He'd ridden boxcars across Texas with a buddy and had three career paths before he was 30.

Born in Pittsburgh on Christmas Day 1903, Fite was 3 when his family moved to a farm near Houston. Tom, his carpenter father, had caught yellow fever working on the Panama Canal. The Texas climate would be better for him, he reckoned, and he settled into a life of farming and violin-making.

Opus 40, Harvey Fite's sculpture, fills Saugerties quarry

Peter Carr, Rockland/Westchester Journal News

Young Harvey rode a horse to school and learned carpentry from his father, but he also loved ballroom dancing, and would squire Houston debutantes around the dance floor. He even considered dance as the first of many career dalliances.

He studied law in Houston but quit after three years. He came east on the recommendation of an Episcopal bishop and studied at St. Stephen’s College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, then a divinity school that later became Bard College, but quit that, too, after three years.

At St. Stephen’s, he was drawn to theater, not theology, and played the brooding Heathcliff in “Wuthering Heights.” He left school and joined a bohemian Maverick community in Woodstock, New York, as a set-building carpenter, living under its theater's stage. He later joined the traveling Jitney Players as an actor.

It was backstage during one performance, the story goes, that Harvey Fite’s life was changed forever, by a discarded wooden spool. Sitting in the wings waiting for his cue in yet another Jitney melodrama, the former Texas farm boy took out his pocketknife and began to whittle, turning the spool in his hands, carving off flecks of wood to reveal a figurine.

It felt right. Like a puzzle piece revealed.

When he was carving, he didn’t have to wait for his cue to speak. He didn’t have to rely on anyone to tell him what to say or where to stand when he said it. This was something he could do on his own: One man made this.

He soon quit the troupe and spent the winter of 1933 teaching himself to sculpt in a borrowed barn in Princeton, New Jersey. Years later, he’d learn under a master carver in Italy, and would take a sabbatical trip to India and Cambodia to study sculpture, but otherwise, he was largely self-taught, a process he called “trial and lots of error.”

Harvey Fite learned as he went along.

It was 1934, and Dean Donald Tewksbury had big plans.

He had arrived a year earlier from Columbia University, which had taken over St. Stephen’s in 1928. The new dean would turn the curriculum on its head, emphasize the arts, take the divinity school in a new direction with a new name: Bard College.

He needed someone who knew the area, knew the school, could construct a theater and teach drama. Tewksbury learned he needed Harvey Fite, even though Fite had left before graduating and had shifted his focus from theater to sculpture.

Perhaps it was because he was self-taught and didn't know what he didn't know. Perhaps it was the arrogance of the artist. Or maybe it was just his natural self-esteem, which he didn't lack. But for whatever reason, the 30-year-old Harvey Fite said he would create a Fine Arts Department for Bard College.

But he had one condition: He wanted to teach sculpture.

Tewskbury agreed, and for 35 years, until he retired in 1969, Harvey Fite used his self-taught skills to teach sculpture at Bard. Another piece of the puzzle clicked into place.

Von Bramer Brothers' bluestone in Saugerties was among the finest in the area, cut from its Upper Devonian era seam in flat slabs and carted off to become the sidewalks of New York City and beyond.

Then came concrete, consigning bluestone to patios and dooming Catskill quarries.

When he bought the mothballed quarry in High Woods in 1938, with all the bluestone a sculptor could ever possibly need, Fite's life puzzle began to take shape.

He spent his school years in tweed, teaching sculpture and the arts, his summers shirtless in the Hudson Valley sun at the mercy of persistent Catskill horseflies, and much of the rest of his time in the vibrant Woodstock art scene, serving on the board of the Woodstock Artists Association.

Harvey was a Woodstocker, says Cederquist, whose fascination for his former neighbor — the man who told him no, but for the best possible reason — has never dimmed.

"In his presence, you never felt smaller than him," Cederquist says. "He was highly revered and he had many students that became Woodstock artists and artists elsewhere. He had a way, you would not feel threatened, looked down upon, anything like that."

And his work ethic? Ridiculous. He was out on the rocks at first light in summer, and labored till he lost the light at dusk. He insisted he could teach himself the best way to make the pieces fit, even if there was no roadmap.

That, too, was Harvey's way.

Caroline Crumpacker, the executive director of the Opus 40 nonprofit, has a new appreciation for the way Fite's mind worked, his ability to see possibility where others saw only chaos.

When Fite looked out over the ruined land he had bought, he, too, saw acres of offcast rubble. But his mind took in the scarred topography and imagined his sculptures arrayed on tidy terraces and pedestals.

He would cut massive blocks of bluestone, a rock that won't abide intricate carving, and create stirring figurative pieces: "The Bather," a beautiful woman by a pool; "Flame," a woman whose hands stretch, flamelike, to the sky; "Quarry Family," with its unfinished child. Each would have a pedestal, take its place in the monument that was taking shape in Fite's mind.

It's the kind of openness to opportunity that Crumpacker wants her high-school daughter to take to heart, her generation having learned to make the best of challenging situations during the pandemic.

“It's not just what first meets the eye, it's what you can do with it. It's: 'How do I meet this challenge and make it into something better? How do I make this of use to other people?’" Crumpacker says. "I feel like that's on us, whether we choose it or not. And he's someone who chose it."

But Harvey Fite had a problem, the solution for which led him to the most courageous decision an artist can make.

The bigger Opus 40 got, the smaller his statues looked when placed upon it. "Flame," the half-ton work designed for the most prominent position, was swallowed up by the enormity of the canvas on which it was placed.

Gradually, Fite realized that the canvas he was creating would become the art itself. And he searched for a proper focal point sculpture, one large enough to make a statement. When he found it, he showed Fite-ian patience until he could make it his own.

He had seen a 15-foot, 9-ton bluestone column in a nearby streambed, but the priest whose land it was on wanted too high a price. Fite waited a dozen years, till the priest died, and approached his successor. The stone was his.

Fite had planned to carve the piece in place, but once he got it in upright — using techniques like those employed by obelisk-raising Egyptians — those plans fell away. After much thought, the sculptor came to the difficult decision that he could not improve on what nature had delivered. He did not raise his chisel. The only marks on it are from the chains needed to hoist it into position.

"The decision not to carve it was a huge, major decision, and the right one," says Tad Richards, the now-81-year-old son of Fite's wife, Barbara Fairbanks.

The man whose only tools were muscle, hammer and chisel was done in by an internal combustion machine and gravity.

On May 9, 1976, Fite was cutting the grass, guiding his sit-down mower between the house-side pool and the lip of his sculpture. Now 72, his dark hair silvering with age, he eased the mower forward, toward the edge of a 14-foot wall that had been one of the first he'd built inside the southern edge of the quarry.

He shifted the mower into reverse and let out the clutch, only to have the machine lurch forward — and down.

Barbara Fairbanks, Fite's wife, only knew he was gone when he didn't come in at the end of the day. They found him later, dead, pinned beneath the machine and the quarry floor.

Without Harvey and his vision, Barbara insisted that the work of creating Opus 40 ended with its creator, frozen where it was on May 9, 1976, when Fite laid down his rocks and ropes.

In September 2012, John Cederquist's phone rang. It was Tad Richards.

A series of storms had washed out a wall at Opus 40, he said. Could John come by and take a look to figure out what should be done?

The man who was once a boy made his way to High Woods from Woodstock, along roads lined with sugar maples and birches and American beeches. When he arrived, he stood on the upper deck at Fite House, looking down at what nature had done to the man's work.

"It was just earth-shaking, the idea that this thing could melt into the ground," he says.

Then something occurred to Cederquist about where the collapse had taken place.

It was, he says, at the very spot where Harvey Fite died.

Expert stone-wallers look at Opus 40 and say the walls are too straight. They should lean back a bit, to foil gravity's pull. That's what Sean Adcock, a world-class stone-waller from Wales said when he arrived to survey the damage from the 2012 storms.

But after three weeks walking every inch of Opus 40, he gave Richards the answer he had hoped for.

We'll build it back, he said.

Harvey's way.

Reach Peter D. Kramer at pkramer@gannett.com[4] or on Twitter at @PeterKramer[5].

References

- ^ the boy (bit.ly)

- ^ Share on Facebook (www.facebook.com)

- ^ Opus40.org (www.opus40.org)

- ^ pkramer@gannett.com (eu.usatoday.com)

- ^ @PeterKramer (twitter.com)

from GANNETT Syndication Service https://ift.tt/2Zd6sw8

Post a Comment

Post a Comment