MILWAUKEE – On a sunny November day in 2018, hundreds of Wisconsin Army National Guard members crowded into the atrium at Green Bay’s Lambeau Field.

The soldiers would soon deploy to Afghanistan as “guardian angels,” providing security for U.S. and Afghan forces. Commanders and public officials took turns at the podium to wish them well.

“There is no greater treasure in Lambeau Field than the brave men and women who sit before you, ready to stand before the enemy a world away,” said then-Lt. Gov. Rebecca Kleefisch.

All the soldiers would go overseas together. All would return home safely.

But four of the men at Lambeau that day — James Swetlik, Eric Richley, Evan Olson and Logan Collison — would not live more than 18 months after returning to Wisconsin, each dying by suicide.

Evan would take his life one week after attending Eric’s funeral. Logan died five weeks after speaking at Evan’s service.

When Logan died, he left his family a letter, assailing the Guard for not doing enough to prevent and acknowledge the suicides within the force.

Eric’s mother, Kathy Richley, agreed: “It’s important for people and, more importantly, for our government to get off their asses and do something. We’re losing sons and daughters.”

Suicides have been a long-standing problem in the military: Four times as many veterans of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars have died by suicide than in battle.

But the suicide rate in the National Guard has been especially troubling, higher on average over the past five years than the rate among full-time and reserve military personnel. In 2020, 120 Guard members nationwide died from suicide, up from 90 the year before.

An investigation by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, part of the USA TODAY Network, found that as America increasingly leans on the Guard to fight overseas wars, provide security at protests and even drive public school buses, Guard leaders and lawmakers have failed to keep pace with the greater mental health burden facing the soldiers.

Guard units across the country have been called up more in the last year and a half than in any 18-month period since World War II, and there’s no cap on the number of times a soldier can be activated. Some families who lost soldiers to suicide say they are frustrated that the Guard markets itself as a part-time commitment.

“I see these posters that say, ‘Full-time student, part-time soldier’ — it’s just not true,” said Linda Collison, mother of Logan.

Interviews with Guard members, families and military suicide experts reveal soldiers struggling to access basic mental health care. In Wisconsin, the Guard has only three social workers for about 9,400 members.

Unlike full-time military personnel, Guard members don’t live on bases; they’re spread out across the state, making access to military resources difficult. As a result, Guard members must rely on a patchwork of programs that is difficult to navigate. Families said they have spent hours on the phone with the Veterans Administration or the Guard trying to get help; several families said they were ultimately given incorrect information or told they would have to wait months for an appointment.

“What really needs to be established is a one-stop shop, where they say, ‘We don’t care what your question is, you call this Guard number, and they’re going to direct you to the right person,’” said Douglas Hedman, a former Wisconsin Army Guard chaplain.

Daniel Hokanson, chief of the National Guard Bureau, the federal agency overseeing state guard units, declined requests for an interview but issued a one-paragraph statement that said Guard members themselves can take a variety of steps to prevent suicides, including talking to military friends and making mental health a priority.

“It can be reaching out to your leadership, your chaplain, your healthcare provider, or your family — or all of the above! — if you’re struggling. It doesn’t matter which steps you take first — it only matters that you take them,” the statement said.

Other Guard leaders point to various programs designed to help struggling soldiers, but they acknowledged efforts need to improve.

“We have to train our first-line leaders to do better,” said Rear Admiral Matthew Kleiman, who leads the bureau’s suicide response program.

Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers, the commander in chief of the state Guard, said in an interview, “One suicide is unacceptable, and four is four times unacceptable."

But he offered no new initiatives, saying current prevention and support programs are working. "At the end of the day, I believe we are headed in the right direction,” he said.

Maj. Gen. Paul Knapp, Wisconsin’s top Guard official, said in an interview that the state force investigates all suicides and has also opened a separate inquiry into the 127th infantry unit, the 650-member force in which four soldiers died by suicide.

“It breaks my heart to lose a service member from our formation,” he said.

But when the Journal Sentinel requested records related to the investigations, the Wisconsin Guard wouldn’t release them, referring the news organization to the national bureau. A request there is pending; the wait-time for such records is up to two years.

Knapp would not say how many Wisconsin Guard members have died by suicide over the past five years, citing guidance from the federal bureau. The Journal Sentinel asked the bureau for the data, but the request was denied.

When told how the Journal Sentinel was denied suicide records and data, Dwight Stirling, a University of Southern California law professor and a leading expert on the Guard, said: “It is shocking that the National Guard leadership is not open and honest about how it investigates suicides. The investigations are not state secrets or sensitive information that must be hidden from public view.”

Though it is difficult to say why any one of the Wisconsin men died by suicide, the Guard was central to their lives, and three expressed frustration with their experiences.

Specialist Evan Olson, a 24-year-old from Waunakee, had a penchant for trivia and wore red, white and blue every Fourth of July. Specialist Logan Collison, 21, was an exceptional artist and wanted to be a history teacher. He was from Oshkosh. Specialist James Swetlik, a 23-year-old from Appleton, enjoyed traveling, at one time working as a cross-country truck driver.

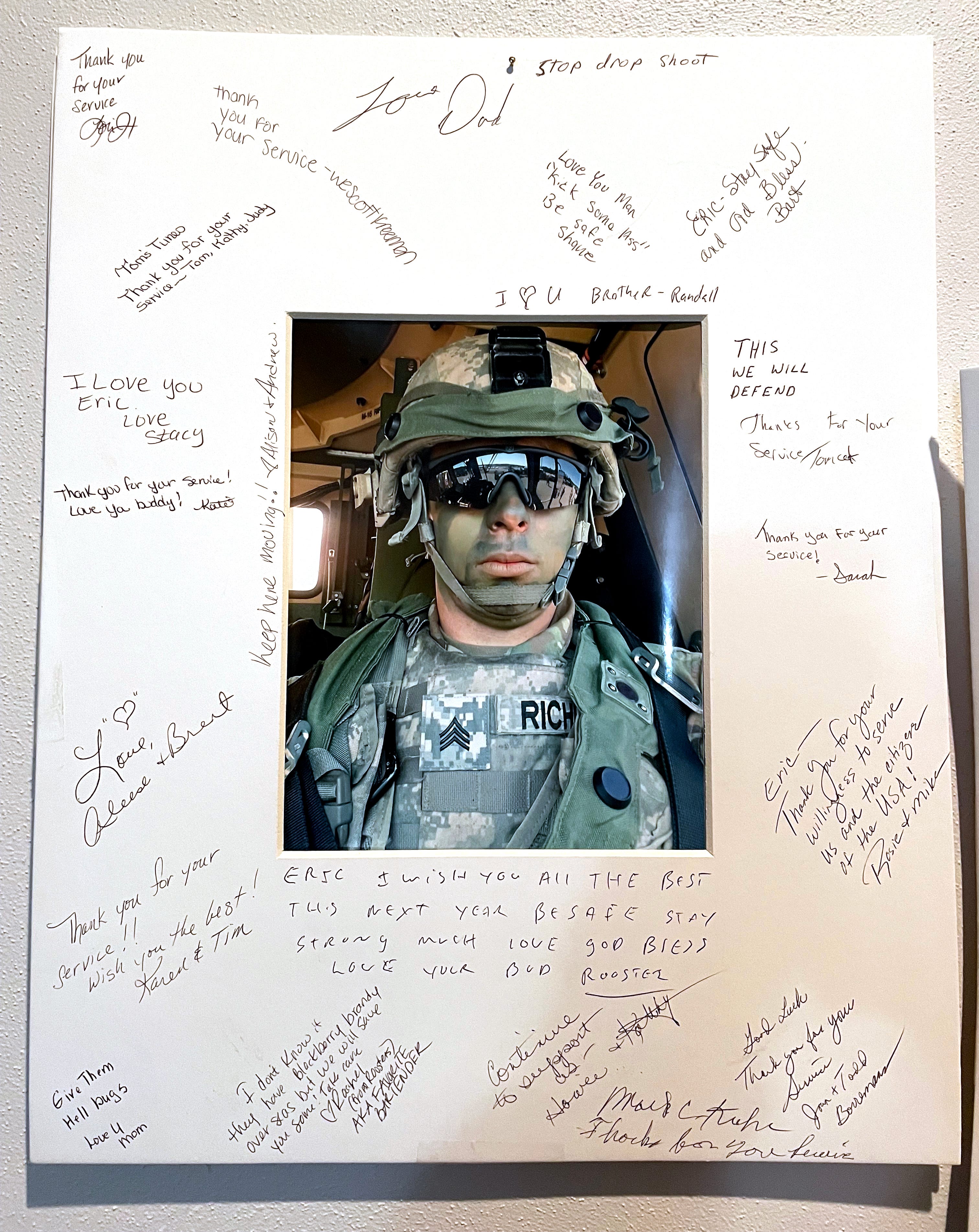

Sergeant Eric Richley, at 32, was the oldest of the four. He lived in Nichols and was the father of two boys, ages 7 and 9.

Now, Richley’s ashes are in an urn on the fireplace mantle in his mother’s home, next to a folded American flag.

Six months after the Lambeau sendoff, the Wisconsin Army Guard soldiers, including Evan, Logan, Eric and James, were not in Afghanistan as “guardian angels” as promised. They weren’t crisscrossing the country on a variety of security missions.

Instead, members of the unit spent much of their time at a base surrounding the Jalalabad airport, in the eastern part of the country. For at least three of the men — Evan, Logan and Eric — hours were spent filling large bags with desert sand to fortify buildings there.

Their mission had shifted because of a drawdown in troops that had begun months before they had arrived. U.S. envoys were in talks with the Taliban about how to end the war, and American forces were pulling back in exchange for assurances that Afghanistan wouldn’t become a breeding ground for Islamic militants.

“I don’t think it was what anybody expected it to be,” said Adam Zuehl, a Guard member who deployed with the four Wisconsin soldiers. “Say you’re practicing and playing all year for the big game, and then once you get to the game you’re benched and told you’re stuck on the sidelines as a water boy.”

While changes are common in military missions, some soldiers became frustrated.

“We kept training and training and training and then at some point guys just felt that the mission lost its purpose,” said Joe Thompson, a former Guard infantryman who also served on the deployment. “It started crushing morale.”

Thompson said the soldiers leaned on each other for support.

“It was like waking up and being with a family of 18 dudes,” Thompson said. “Like if someone went to dinner without you, you felt like they cheated on you, like it was the worst thing in the world. Everyone’s just extremely close in that kind of environment. That’s all you have.”

Afghanistan brought Logan, the artist, and Evan, the trivia buff, especially close.

They met as students in the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh’s ROTC program. Now they were together in a platoon that dubbed itself “Blacksheep” because it was a mix of soldiers from different companies.

Logan’s job was supposed to be driving armored vehicles that transported troops and protected them from roadside bombs. Evan was trained as a radio operator to help commanders stay in contact. He amused fellow soldiers with a random “fact of the day” he wrote on a whiteboard each morning.

James was also stationed at the base, but his mother, Emily Swetlik, said she doesn’t know what his duties were.

Eric Richley, the only father among the four men, was also a radio operator. He would later say he had an experience that would haunt him long after he returned home.

According to his mother, Kathy, and best friend, Jerry Fuss, Eric said on multiple occasions that he was involved in an attack that killed 25 Afghan civilians, including women and children.

Media reports at the time detailed a drone strike by U.S.-led Afghan government forces in the Nangarhar province, where Eric was stationed, that killed about 30 civilians who had gathered to harvest pine nuts.

It is unknown whether Eric was referring to that attack or a different incident.

According to Guard platoon leaders, the Wisconsin unit did not conduct drone strikes itself, but it did work with NATO and military forces that were involved in such attacks.

Eric’s mother said he felt tremendous guilt about the attack that he described, especially about the children who died.

His mother recalled him asking: “What if it had been my kids that somebody did that to?”

All four men — Logan, Eric, Evan and James — returned from Afghanistan in November 2019. They landed, along with others in their unit, first in Texas, where they were greeted on the tarmac by senior Wisconsin Guard leaders.

“Thank you for what you’ve done,” Command Sgt. Maj. Rafael Conde told them. “You’ve made a difference not just in Afghanistan. You’ve made a difference in our society as well.”

Two weeks later, the group flew home, touching down at Camp Douglas in rural central Wisconsin. Family members greeted them with signs reading, “My hero is home” and “Welcome home brother.”

Several weeks later, the soldiers and families gathered at an armory in Manitowoc for a post-deployment debriefing called a yellow ribbon event, with informational booths providing a variety of services, including materials about college financial aid and health care benefits. One requirement was that soldiers briefly stop by a mental health booth and speak with a specialist.

Eric decided to skip the debriefing. “We’re done. I’m done,” he said, according to his mother, Kathy.

She recalled that he was frustrated with the Guard and his time in Afghanistan, saying he said that “everything that could go wrong, did go wrong.”

He didn't re-enlist and went home to Nichols, a village of 300 people surrounded by dairy farms in northeastern Wisconsin. He landed a job as a machine operator at Rollmeister, a company that builds maintenance equipment for paper mills. He worked overtime shifts throughout the summer of 2020 but wanted additional money to support his family, his parents said.

Persistent ringing in his ears also bothered him. His mother said it started on his deployment, when he was exposed to loud artillery fire. The ringing affected his sleep, and he was exhausted and always seemed on edge.

"I think that's when he started drinking more," she said. "It helped him relax, where he could put his head on a pillow."

Forty miles south of Nichols in Oshkosh, Logan spent much of 2020 trying to get caught up in school. He was enrolled at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, studying to be a history teacher and living in a nearby apartment.

But in the spring and summer, he was activated three times for in-state missions. He worked the polls in Green Bay during the presidential primary, provided security in the same city after the George Floyd killing and responded to the social unrest in Kenosha following the Jacob Blake shooting. He didn’t have to drop any classes, but he struggled to balance coursework and Guard duties, his parents said. Every time he started to move ahead in one area of his life, he’d be called up by the Guard and set back again.

Meanwhile, 90 miles to the south, Logan’s close Guard friend, Evan Olson, was living with his parents in Waunakee, a suburb of the state capital of Madison.

Evan’s family said he struggled with isolation brought on by the pandemic. He missed his Guard buddies. He wanted to return to school, but he didn’t want to do online learning. He found a job as a laborer at nearby Hottmann Construction.

He told family members he thought he wasted a crucial year of his life in Afghanistan, on a mission that accomplished nothing.

“He felt like what he did was useless,” said his father, Eric Olson.

But of the four Wisconsin men readjusting to civilian life that summer, James Swetlik perhaps struggled the most.

He moved in with his parents in Appleton, a hub of the state's papermaking industry, and took a job at a local Ace Hardware.

One soldier who served with him, Robert Kniprath, described James as shy, quiet and thoughtful who didn’t always conform to “the typical mold of a U.S. infantryman.” He said James “never sought conflict with others, which is quite a contrast to the typical Alpha-type that serves in the line of work that we engage in.”

The pandemic lockdown troubled James, his mother recalled. Guard events he had looked forward to were canceled.

James fell into a depression, his mother said. He didn’t contact a private therapist or reach out to the Guard or any military resources, she said.

He had dealt with depression in the past and had always been able to pull himself out of it, she said. But this time was different.

James was the first of the four to take his own life. He died on a date sacred to many Americans and one that prompted the war in which he fought: Sept. 11. He was 23.

Four days after James Swetlik’s funeral, Evan Olson posted the obituary on his Facebook page.

“Rest easy brother,” he wrote.

The next day, Logan posted it.

“I want all my vets out there to do a buddy-check,” he wrote on Facebook. “Reach out and talk because you never know what someone is going through.”

Eric Richley mentioned James’ death to his father, Dale Richley.

“Now why would someone go and do that?” Dale recalled asking him.

“I don’t know, dad,” Eric said.

In the ensuing months, Eric continued fixing up his house and working overtime. But the ringing in his ears continued and sleep remained elusive. He tried to get an appointment at the nearest VA hospital, his mother recalled. He was told it would be two months before he could be seen. Eric never made the appointment, telling his mother that if it was going to take that long, he might as well cope on his own.

He self-medicated, trying aspirin, alcohol and marijuana. Smoking marijuana was the only thing that calmed him, she said.

Eric frequented the bar next door to his house, Rooster’s, owned by his friend Jerry. The pair shot pool between bottles of Miller Lite and double orders of fried cheese curds.

On the night of Nov. 29, 2020, things looked darker. He sent a series of texts to his mother, some rambling, some questioning whether he was a good son.

His mom tried to call, but Eric didn’t answer. A few minutes later, she texted him back: “I totally understand. Nighttime, quiet time for thinking, time for reflecting on life. No regrets, Eric. Just lots of family love.”

Eric responded, texting: “Why is it I’m so nice? Granted, I can be very f---ing mean. I’ve seen what I’m capable of and have no f---s given, but why do I let everyone walk on me?

“I can put a bullet in someone’s chest, call in an air strike killing 25 confirmed kills and not have one, not one f--- given and sleep at night. Yet, I’m too nice,” he wrote.

“I love you,” she replied. “Be strong.”

“I love you,” he wrote back.

The next morning Eric was supposed to meet his father at his father's house to clean the garage. He didn't show up, and so Dale got in his truck and drove over to his son's house. He found him alone, in the living room, slumped in a chair. A gun was in his hand; a beer bottle was between his legs.

Eric’s funeral was held in Little Chute, in northeast Wisconsin, on Dec. 5, 2020. It was a drill weekend for Guard members, but more than 80 were released early to attend.

After the funeral, family, friends and about a dozen Guard members gathered at the nearby home of Eric’s father. They lit a bonfire in the backyard and shared stories between cigars and whiskey. Eric’s favorite classic rock music played in the background.

Evan Olson attended the funeral and bonfire, then that night drove 2½ hours south back to his parents’ house in Waunakee.

He had been struggling with depression intermittently throughout 2020, his parents said, in part because the COVID lockdowns prevented him from being able to see friends or drill regularly.

Eventually, he told his mother that he needed to talk with a therapist.

In middle school, his mother said, Evan had been diagnosed with ADHD, depression and anxiety and was prescribed the antidepressant Zoloft and the ADHD-medication Adderall. But when he joined the National Guard, he stopped taking the medications, believing they were prohibited, a common misconception 1[1].

He had re-enlisted in 2020 for another six years and didn’t want leaders to know he was struggling. His mom, Juli, tried to find a therapist, calling numbers provided at the yellow ribbon debriefing. She said she was bounced around 2[2] and that a VA representative eventually told her Evan was not eligible for care because he was in the Guard and not in a full-time force.

But Evan served overseas and should have been eligible. His mother also said no one could answer her questions about medication.

The December night that Evan returned from Eric’s funeral his father asked where he had been.

“Well, we went to Little Chute,” Evan replied, his father recalled. “One of the guys in my unit killed himself.”

His father paused, then looked directly into his son’s eyes.

“Evan, don’t ever, ever think of doing that to your mom and dad and our family.”

“Dad,” Evan said, “I would never do that.”

Seven days later, he found Evan in his bedroom, dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Dozens of Guard members in their blue uniforms gathered at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church in Waunakee for Evan Olson’s funeral. It was a week before Christmas, on Dec. 18, 2020.

It took an hour for the crowd to make its way through the receiving line. After his family said their goodbyes to Evan, about 20 Guard members filed to the front of the church and stood at attention in front of the casket as a funeral official slowly closed it.

Following a few words from the priest, Logan approached the pulpit. He was the only non-family member to speak.

“For those of you who don’t know me, I’m Specialist Collison,” he said. “Olson was in my squad, known him for a couple of years now, and he was someone very important to me. He was one of my best friends on deployment.”

He then read a poem he found online. It began: “Shall I wither and fall like an autumn leaf, From this deep sorrow — from this painful grief?”

After the funeral, family and Guard friends gathered at Rex’s Innkeeper, a local supper club. Logan attended with his brother, Ryan.

Logan told his brother he felt guilty he didn’t recognize any warning signs about Evan. “He felt within himself that he had failed his best friend,” his brother said.

Logan also told family members he thought the Guard didn’t view low-level soldiers as human beings. According to family and Guard friends, Logan himself had struggled for months with a company leader who he felt targeted and belittled him. Logan tried to transfer out of his company, family members said, but his requests were denied.

After seeing his schoolwork at UW-Oshkosh interrupted by multiple deployments in 2020, Logan was trying to return to a normal life at the beginning of 2021. He once again signed up for classes.

Then, on Jan. 6, rioters stormed the U.S. Capitol. A few days later, when Logan was visiting his sister in Michigan, he received a call from a Guard commander: It was the fourth time since returning from Afghanistan that Logan was being activated.

With school starting in a couple of weeks and the three suicides weighing on him, he did not want to go, family members recalled. He was emotionally and mentally depleted, physically exhausted. He also didn’t want to face the leader who made him feel worthless.

After several requests, he eventually got a waiver and didn’t have to report.

According to his family, Logan increasingly felt like a political pawn. He said the Guard had become an “easy button” that politicians pushed anytime there was a problem they didn’t know how to address.

On Jan. 19, 2021, Logan and others were scheduled to report to Camp Douglas for a monthly drill. The night before, he called his mother to check in and texted a couple of friends. His last text, in the early morning of Jan. 19, was to a close childhood friend. He told her he was going to see “Olson,” a reference to his friend Evan Olson who had died by suicide a month earlier.

Logan drove his Honda Civic coupe a few miles away from his apartment and killed himself with a rifle. He was found by police hours later.

According to his parents, he left behind a letter he had started three days before in a Google Doc, lambasting Wisconsin Guard leaders about how they treated soldiers and didn’t address the suicides in his unit.

His parents gave the letter to Wisconsin Guard officials, who said they have been investigating his death and allegations for 10 months 3[3]. The officials did not say when findings are expected.

Logan’s mom, Linda, said she believes his suicide was one of purpose.

“I’ve felt from the very beginning that Logan fell on his sword,” she said. “He had no safe place in the Guard to turn to report problems and get direction.”

Still, she said, “He was so proud to be a member of the armed forces.”

In the letter, he agreed.

“If I had to do it all over again,” he wrote, “I would still sign up.”

On a Saturday morning this past October, the mothers of Logan, Evan and Eric, along with about 180 others, gathered in Madison to march around Lake Monona.

They wanted to draw attention to military suicide and honor their sons, who did similar marches as infantrymen.

The mothers each carried a sign of their son’s photo along with their dates of death.

Nine miles into the 14-mile march, Kathy Richley, Eric’s mother, was out of breath, pausing on the sidewalk. “If Eric can do it, so can I,” she said.

After the march, she and others called for action. “There can be some redemption if changes are made,” Logan’s mother said, “but for things to stay the same is worse.”

In an interview, Knapp, Wisconsin’s top Guard official, said the force already offers a variety of services, such as a multiweek mental health class for members and a support group for families. The Guard, he said, is also revamping its deployment debriefing program to include smaller group discussions and incorporate families of soldiers who have died by suicide.

The Guard wanted to expand the mental health class to its entire force, but state lawmakers last year rejected a $1.6 million request to pay for it.

For the families of the four soldiers, there's a new reality: life without their sons.

Evan's father, Eric, spends many of his days at the Ice Pond, an indoor ice rink in Waunakee, home to the local high hockey team, which he has coached for 12 years. He coached Evan from age 4 through high school, spending countless hours together at the rink.

Now, he said, everything there reminds him of Evan, and he sees his son in every young face.

With his son’s death, he wonders how long he can keep coaching, but “I know Evan would want me to continue.”

At one recent practice, after all the players left, Eric Olson kept his skates on. No one was on the ice or in the bleachers.

But Eric stayed, slowly circling the rink, over and over.

Reach reporters Katelyn Ferral and Natalie Brophy: kferral@gannett.com and nbrophy@gannett.com

References

- ^ a common misconception 1 (eu.usatoday.com)

- ^ bounced around 2 (eu.usatoday.com)

- ^ for 10 months 3 (eu.usatoday.com)

from GANNETT Syndication Service https://ift.tt/3nsRiMJ

Post a Comment

Post a Comment